Scroll down to learn more

The EU funded EBO-SURSY Project has been rolling out in 10 countries since 2017 to foster collaboration between human and animal health professionals and help countries become more prepared for animal disease outbreaks such as Ebola. Focusing on 5 viral haemorrhagic fevers and coronavirus, it has had promising results, building a better future for us all.

By understanding wildlife health, we can protect the health of other animals, humans and Earth’s ecosystems.

Ebola is only one example. 60% of infectious diseases that affect people are zoonoses, meaning they are of animal origin.

On average, only 50% of infected humans and 10% of infected gorillas have survived.

In Central Africa, the virus is estimated to have reduced gorilla populations by

one-third.

Since Ebola was identified in 1976 in the DRC, more than 30,000 humans and tens of thousands of animals have been infected.

December 2013. A two-year-old boy from a remote village in Guinea passes away, presumably after being in contact with bats, sparking the first Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

Protecting wildlife,

An outlook on the

EBO-SURSY Project

protecting our future

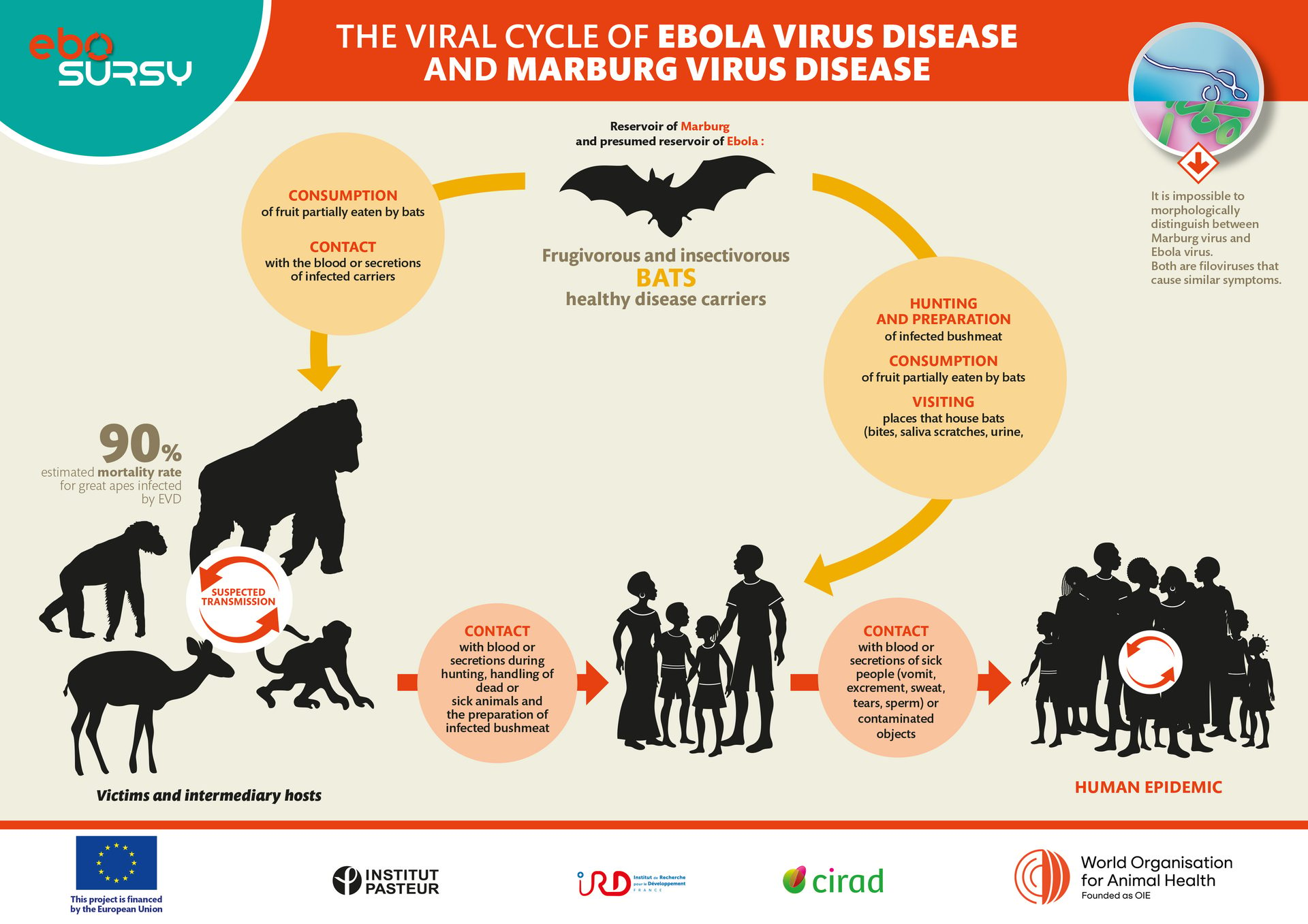

How can the health of wildlife impact the health of human populations? Boundaries between species are much more blurry than it seems. At the animal-human interface, where wildlife and humans meet, pathogens can jump from one species to the next through a phenomenon called zoonotic spillover.

©WOAH/S. Muset

The blurring lines between species

©WOAH/S. Muset

The more humans come into contact with wildlife, the more likely they are to face spillover. And this works both ways: endangered species that are approached by humans are at higher risk of contracting dangerous human pathogens, or reverse zoonoses. This is particularly worrisome for endangered or vulnerable species, as zoonoses can increase biodiversity loss.

Wildlife health is everyone’s health

©WOAH/S. Muset

Wildlife species are essential to maintain balanced ecosystems. For example, bats pollinate plants, disperse seeds and protect other animals from diseases by eating insects. When wildlife species die of zoonoses or reverse zoonoses, it can set a ripple effect through the environment, impacting human health and the very survival of ecosystems.

Over millennia, human and wildlife health have consistently been bound together, facing zoonotic threats.

Viral haemorrhagic fever outbreaks in Africa

Marburgh virus disease

1967-today

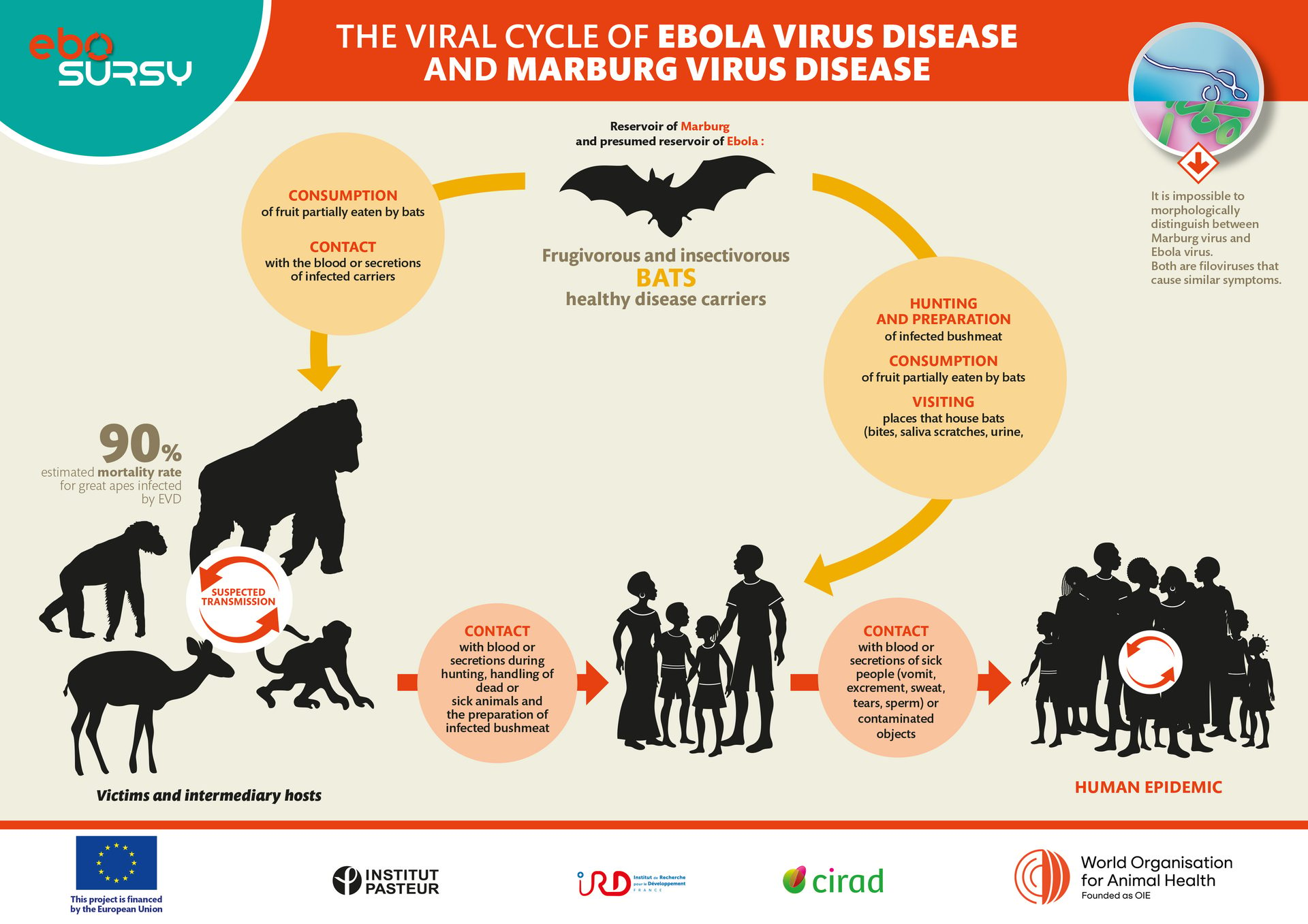

- Originated in bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus)

- Transmitted to humans, non-human primates and duiker antelopes

- Through hunting and preparation of infected bushmeat, consumption of fruit partially eaten by bats, visiting places where bats live

590 reported human cases worldwide

81% mortality rate in humans

Click to unveil

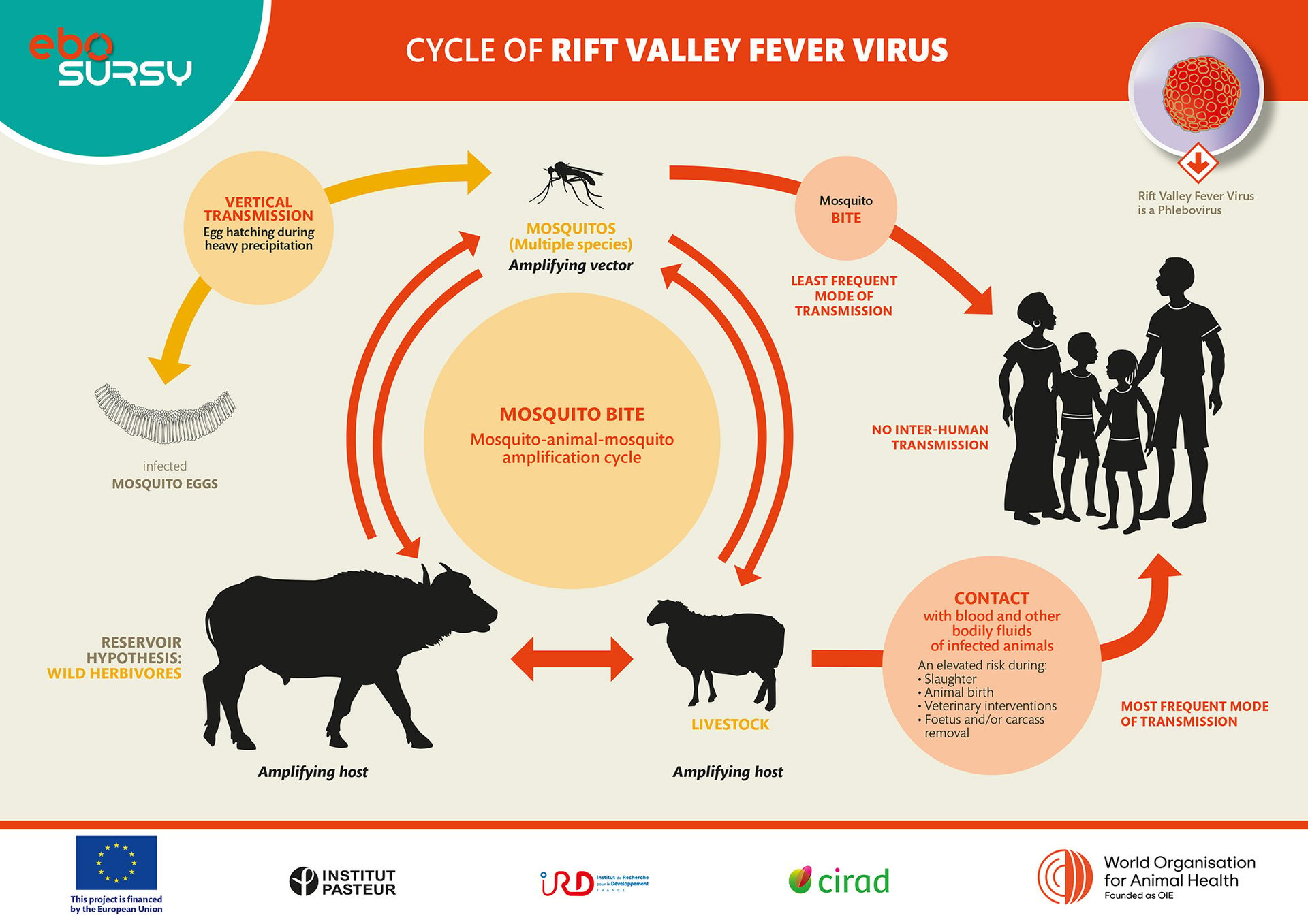

Rift Valley fever

1910-2019

- Originated in domesticated animals (cattle, buffalo, sheep, goats, camels, etc.) and mosquitoes (Aedes, Anopheles, Culex, Eretmapodites, Mansonia)

- Transmitted to other domesticated animals and humans

- Through raw milk ingestion, mosquito bites, domesticated animal-human contact

4,641 reported human cases worldwide

Mortality rates depend on the species:

100% for young lambs and goats

22%

for humans

10% and less for adult goats, buffalos, and Asian monkeys

Click to unveil

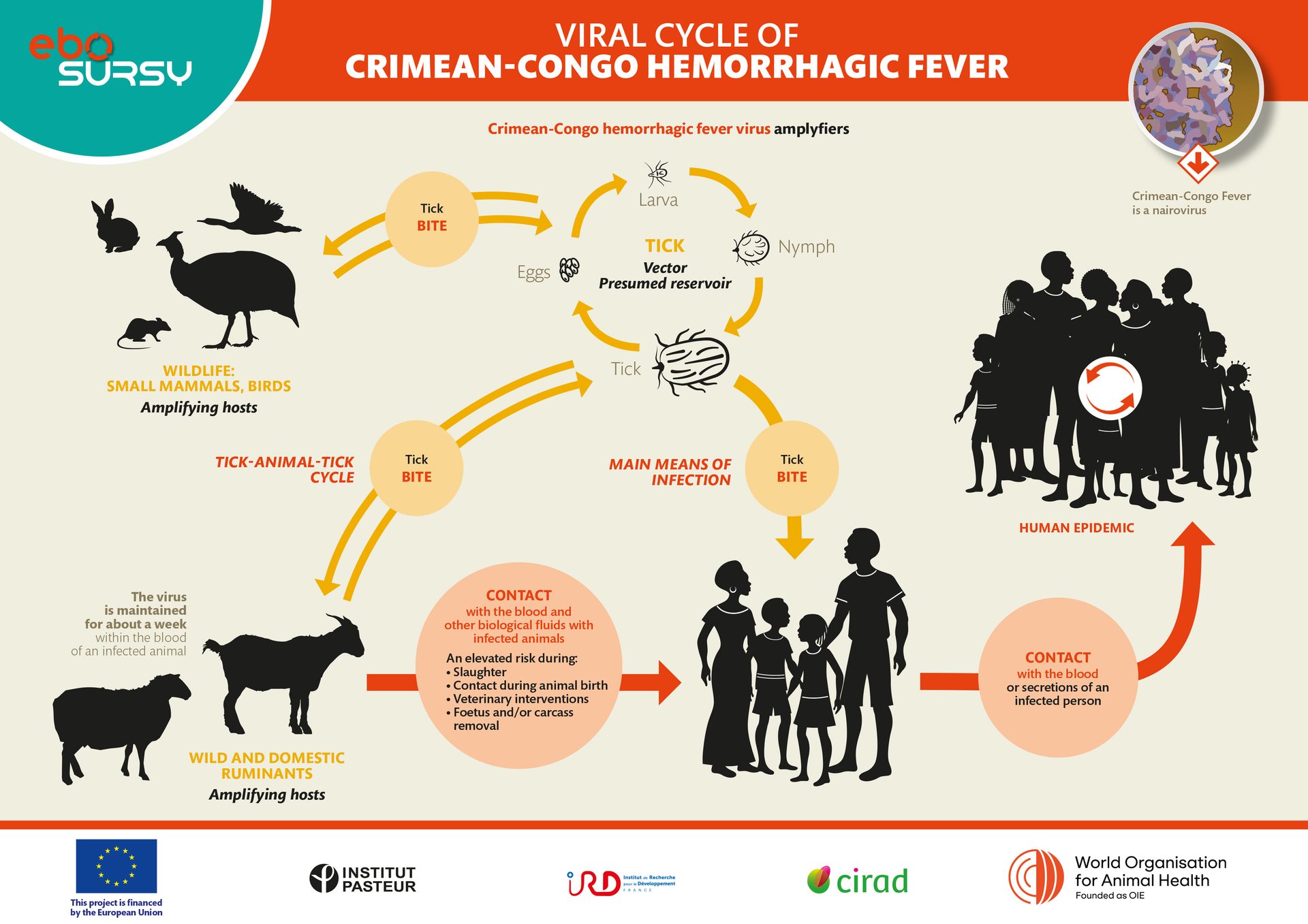

Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever

1944-today

- Originated in ticks (Hyalomma marginatum)

- Transmitted to wild and domestic ruminants, small mammals, birds and humans

- Through tick bites, contact with bodily fluids of contaminated animals and humans

494 reported human cases in Africa

up to 40% mortality rate in humans

Click to unveil

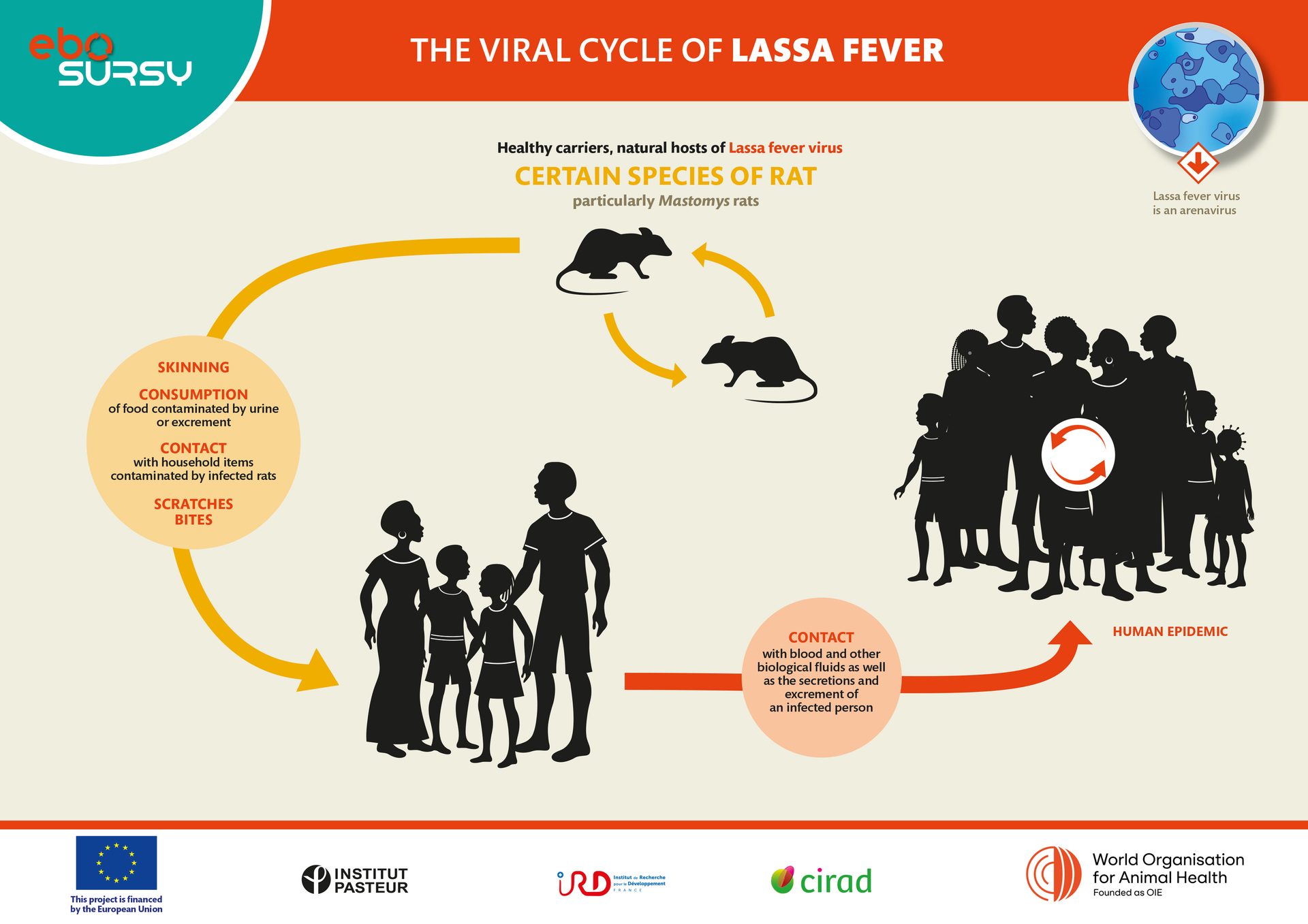

Lassa fever

1969-today

- Originated in rodents (especially of Mastomys genus)

- Transmitted to humans

- Through contact with rodent’s excretions, contact with infected human’s bodily fluids

100,000-300,000

reported human cases per year in Africa

1% mortality rate in humans

Click to unveil

Ebola virus disease

1976-today

- Originated presumably in fruit bats

- Transmitted to humans, non-human primates and duiker antelopes

- Through hunting and preparation of infected bushmeat, consumption of fruit partially eaten by bats, visiting places where bats live

34,945 reported human cases worldwide since 1976

50% mortality rate in humans

1/3 decline of West African gorilla population

90% estimated mortality rate for great apes

Click to unveil

©J.F. Lagrot

Human encroachment into wildlife natural habitats through deforestation, intensive agriculture, mining, or urbanisation, increases human contact with wildlife and fosters hotspots for disease emergence. Once a zoonosis has emerged, it can quickly spread from one country to the next, causing global pandemics.

Our worlds are not separate. When humans eat animal products, when they handle domesticated animals, when they visit wildlife habitats… They can participate in the spread of zoonoses which affect animal and human health alike. In this photo, bushmeat is being prepared for human consumption.

©J.F. Lagrot

Wildlife and human health overlap

Because wildlife health is essential to the balance of our ecosystems as well as to human health, it must be protected through a One Health approach. This means that human health and animal health services must work together to face common threats.

The EBO-SURSY Project is empowering countries to build strong surveillance systems that engage every sector for the benefit of wildlife, ecosystems, and ourselves.

Scroll down to learn about the EBO-SURSY Project

EBO-SURSY: Helping countries build their surveillance capacities

Increase surveillance capacity for diseases in-country.

Raise community awareness on disease prevention strategies and how to participate in surveillance locally.

Strengthen surveillance protocols that help keep communities and animals safe.

©J.F. Lagrot

Because wildlife and human health are intricately linked, the EBO-SURSY Project has been empowering countries and health workers across West and Central Africa since 2017. To help build strong systems for prevention and response against viral haemorrhagic fevers, it aims to:

7 years

10 countries

5 zoonoses:

- Crimean Congo haemorrhagic fever

- Ebola virus disease

- Lassa fever

- Marburgh virus disease

- Rift Valley fever

EBO-SURSY so far…

Using a One Health approach which considers human, animal and environment health as one interconnected system, EBO-SURSY has helped connect and empower people to become informed participants of global health, from grad students, veterinarians, wildlife and public health professional and community members to decision-makers.

Scroll down for more detail

Empowering the animal health workforce

As the response to the 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak revealed, one of the main vulnerabilities in the public health response of the countries impacted was a lack of interconnected and strong human and animal health surveillance systems.

©J.F. Lagrot

To better prevent and manage the emergence of diseases such as Ebola, there are signs we can look out for in wildlife. This monitoring action is called surveillance.

Wildlife surveillance can either be active or passive.

Active surveillance is targeted on a specific disease or species and helps obtain vital statistical information on the disease. For instance its prevalence, geographical distribution, age and sex of the affected species. The better we know the disease, the easier it is to prevent or manage its outbreaks.

Scientific teams sample wildlife feces in Cameroon.

©WOAH/S. Muset

Passive surveillance aims at detecting diseases in wild animals that have already been identified as sick, have been found dead or are acting unusually. Hunters, wildlife rangers, conservationists and local populations are essential in these efforts. The earlier we can detect cases of a disease, the more we can manage its spread.

In a village, a scientist samples a deceased antelope.

©J.F. Lagrot

An efficient surveillance system encompasses both active and passive surveillance, and involves stakeholders all along the chain, from villagers, rangers and conservationists to animal and human health workers.

These stakeholders must be informed and trained to fully play their part in the system, and a clear chain of communication established to help relay information in case of an outbreak.

The people that can help prevent or manage outbreaks in West and Central Africa often lack the technical knowledge, techniques, material or resources to excel in their profession. Additionally, many health stakeholders work in silos, whereas communication and partnerships between sectors using a One Health approach are necessary to successfully combat diseases such as viral haemorrhagic fevers.

To bridge these gaps, the EBO-SURSY Project has been hosting a wide range of capacity-building activities over the past seven years, including training programmes and scholarships. It has given animal health stakeholders all along the chain the means to build robust surveillance systems in their countries, with long-term positive impacts.

©IRD/ N. Vidal

One Health training | Laboratory techniques

Guinea’s laboratories are resilient facing COVID-19 outbreak

©WOAH/S. Muset

One Health training | Ecology of zoonoses

Fostering early detection of diseases through collaboration

700+ professionals

and students trained in laboratory techniques, ecology, epidemiology and surveillance systems

600 health

professionals engaged in improved intersectoral collaboration

30 grants

provided to health professionals to attend One Health and emerging diseases training

Scroll down to find out how the EBO-SURSY Project is raising community awareness of zoonoses

Building trust with communities

Because of zoonotic spillover, humans and wildlife alike are vulnerable to many diseases such as viral haemorrhagic fevers. By looking out for tell-tale signs of zoonoses, including unusual deaths and behaviour in wildlife, local communities are the first in line to alert national Veterinary Services or wildlife authorities. Who in turn can launch investigations and help prevent isolated cases of a disease from escalating into full-blown epidemics.

Informed communities are empowered to protect themselves, other humans and wildlife.

©WOAH/E. Muweza

Why is community engagement vital to prevent zoonotic outbreaks?

People living near or within natural ecosystems such as rainforests are generally isolated and lack access to information on how to protect themselves, wildlife and domestic animals.

To preserve both human and wildlife health, the EBO-SURSY Project reached out to communities through radio campaigns focused on raising awareness on wildlife diseases and prevention strategies.

©IRD/P. Becquart

Key messages from preventive and technical factsheets were incorporated in a radio guide.

In total, 28 communication tools were produced to reach local communities and health professionals.

A specific radio programme was designed to disseminate these key messages.

3 million

listeners in Guinea and DRC

of public service announcements

2,400 broadcasts

60 journalists and youth reporters

trained

73%

of people indicating they listened to EBO-SURSY Radio were regular listeners and followed the programme several times a week

56%

made listening to the programme a family affair

For the radio programme, WOAH partnered with the NGO Radio Workshop, which works with radio broadcasters and youth reporters to engage local communities on critical issues. The programme was broadcast across 11 radio sites that covered forested areas, national parks, as well as some cities in Guinea and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). All areas had been affected during the 2014 Ebola outbreak or more recent ones.

A radio guide was created with One Health principles to help foster similar initiatives in other regions impacted by other infectious diseases, and share guidelines on how to create efficient public service announcements (PSA).

Listener in Yangambi, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Before this programme, when I went for a walk in the forest and found a dead animal, I was happy because I’d just found something to feed my family. It was from these shows that I learned these animals can transmit diseases to us when we touch or eat them.

©WOAH/S. Muset

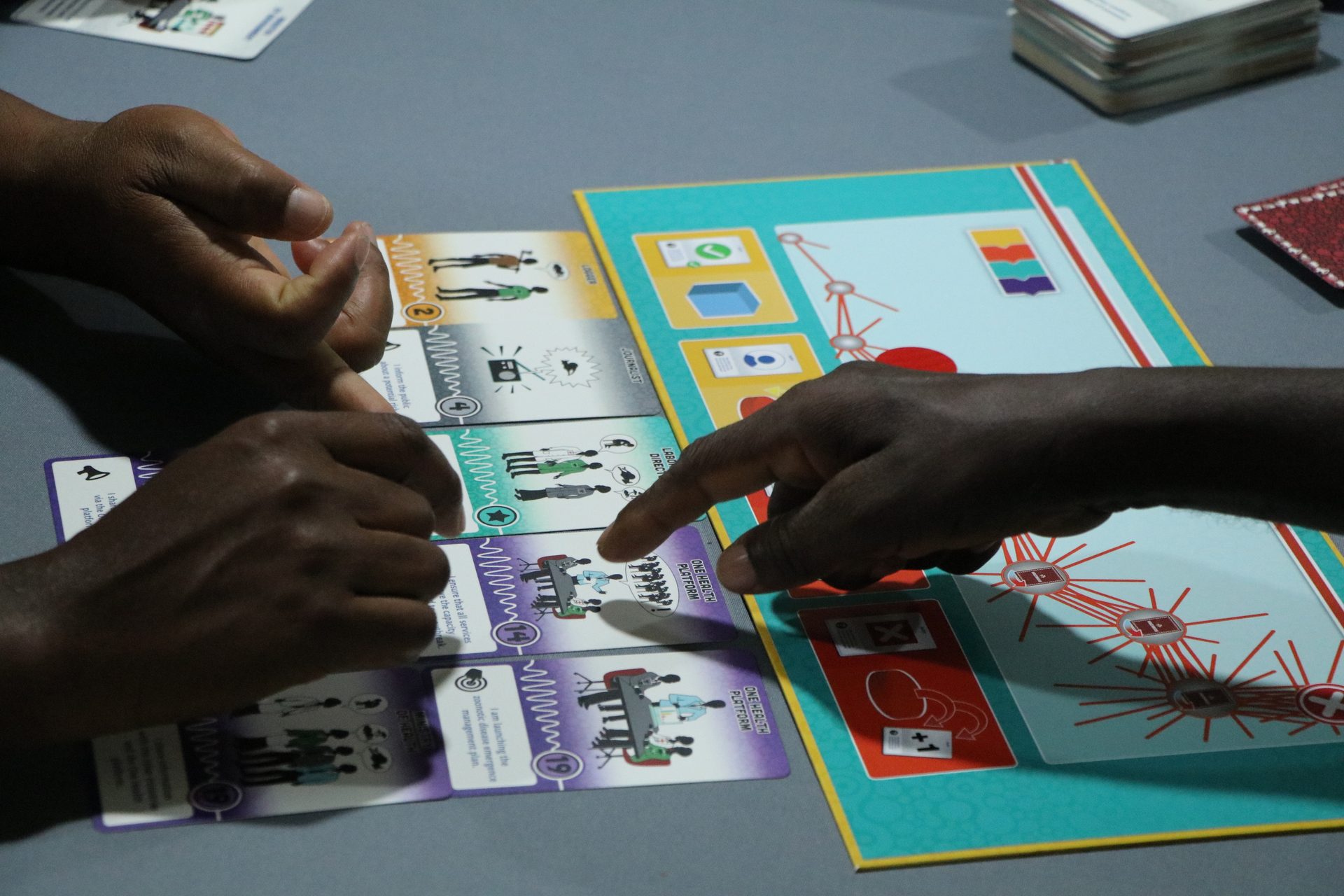

To sensitize surveillance stakeholders all along the chain, from community members to Veterinary Services, the EBO-SURSY Project also disseminated a collaborative game called “Alert” in 10 countries.

©WOAH/S. Muset

40 facilitators representing 3 different sectors were trained in Senegal and Cameroon. Their role was to help disseminate the game to a broader audience.

©WOAH/S. Muset

After their training, the new facilitators tested their skills on 160 students from the public health and veterinary sectors. In the future, the game will be used in universities across the region to train a new generation of veterinarians on One Health.

The Project’s research activities contributed to raising community awareness of zoonoses. When scientists visited remote villages to collect samples, they explained their research and shared information with community members on diseases and good practices to ensure everyone’s health.

Scroll down to find out how EBO-SURSY is helping countries predict and prevent oubreaks

©J.F. Lagrot

Building capacity and raising community awareness are essential steps to establishing strong national surveillance systems, but they are not enough. Countries need masterplans to monitor pathogens and to provide guidance on how to react in case of an outbreak. In other words, they need surveillance protocols.

Predicting and preventing outbreaks

Surveillance protocols may seem simple. However their implementation depend on many factors, including a reliable supply of sampling material, functioning cold chains, efficient laboratories and roads, trained professionals, and even public communications. The financial resources this implies is substantial. Surveillance protocols in some countries are only now being put into place, despite countless outbreaks of dangerous pathogens.

©WOAH/S. Muset

©WOAH/S. Muset

To help national Veterinary Services and wildlife professionals build effective surveillance protocols step-by-step, the EBO-SURSY project held three regional workshops. Some attendee countries also asked for support in holding national-level workshops to refine the draft protocols for their priority diseases. A holistic approach involving professionals from across the One Health spectrum was adopted throughout.

3 new countries

now have Rift Valley fever protocols in place: Sierra Leone, the Republic of the Congo and the Central African Republic.

Ivory Coast

now has a surveillance protocol for Lassa fever.

10 countries

now have experience building surveillance protocols, which can be applied to other diseases in the future.

Other countries that attended the workshops made great progress in developing protocols which may be implemented in the future.

Because efficient surveillance protocols must be grounded in scientific fact, the EBO-SURSY Project organised field investigations and supported multi-scale research, with the aim to provide countries with data-driven predictive models and risk assessment tools such as maps tracking bat migration in the Republic of the Congo, or the capture and sampling of wildlife across West and Central Africa.

©WOAH/S. Muset

From sampling bats or wildlife feces in Cameroon forests to domestic pigs in Guinean farms, the project collected a large amount of data to better understand transmission patterns. All of the data collected has been made accessible on a digital portal, to support knowledge sharing across borders and across scientific institutions.

197 field investigations

were held.

43,000 animal samples and 6,000 human samples

were taken to track diseases at the animal-human interface.

43 studies were published

as a result of EBO-SURSY funded research in the fields of ecology, genetics and socio-economics.

25 methodologies and diagnostic tools

have been improved or developed.

To better understand Ebola virus transmission dynamics and participate in active surveillance of this disease, a team of researchers samples bats–a suspected natural host of the virus.

©WOAH/S. Muset

Samples are sent to the CREMER laboratory in Yaoundé. Over 12,000 samples have been safely stored in this laboratory in recent years. A precious archive that can be studied in case another pathogen emerges.

©J.F. Lagrot

Specimens are weighed and measured, and samples of blood and saliva are collected.

©J.F. Lagrot

Data and conclusions obtained from the analyses are shared with the scientific community through the EBO-SURSY Project data portal and other scientific publications.

©J.F. Lagrot

Follow the bats: a field mission in Cameroon

Sampling takes researchers into isolated forest areas to better understand the modes of transmission of viruses from animals to humans.

©J.F. Lagrot

©WOAH/S. Muset

To bolster communication and knowledge-sharing across different fields, an international symposium was organised in Senegal, in October 2023. National Veterinary Services, scientific partners, EBO-SURSY scholarship recipents, and other global health stakeholders met to engage in discussions on the project’s scientific findings and their implications for strategies in monitoring and managing diseases. Abstracts were published in Virologie to share knowledge and insights with the international community.

Because animal health is our health.

It’s everyone’s health.

New horizons for wildlife health

After 7 years, the EBO-SURSY Project is about to enter a new phase with the support of the European Union.

Over the next five years, it aims to expand its geographic scope to 17 countries and include more scientific partners, as well as more One Health stakeholders. The project will go even further in helping national Veterinary Services set up efficient surveillance systems, and apply scientific findings from phase one into policy, legislation and professional guidance to safeguard health.